Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) Piano Trio in A minor (1914)

Modéré

Pantoum. Assez vite

Passacaille. Très large

Final. Animé

The music of the young Maurice Ravel did not appeal to the contemporary, conservative musical taste of the Paris Conservatoire. For example, he never won the Prix de Rome; and not for want of trying – five attempts between 1900 and 1905. His last attempt (he had reached the age limit of 30) was triaged out because his fugue contained parallel fifths and the last chord contained a major 7th. This Strictly Ballroom-style failure provoked l’affaire Ravel, with even his usually hostile critics affronted that such a distinguished composer should be so perfunctorily dismissed. After the press got their teeth into the fact that all the finalists were students of one particular jury member, the director of the Conservatoire resigned and was replaced by the reforming Fauré (nicknamed Robespierre).

Ravel’s independent spirit sought out new musical and literary genres, such as the Gamelan and the contemporary Russian music that he heard at the 1889 Paris exhibition. Around 1902 he joined Les Apaches (The Hooligans), a group of broadminded literary, musical and artistic contemporaries. The group was joined in 1909 by Stravinsky, and Ravel was commissioned by Diaghilev to write Daphnis et Chloé for the Ballets Russes. In 1913 Ravel joined Stravinsky at Clarens in Switzerland where they jointly orchestrated a piece by Mussorgsky for Diaghilev and Ravel was shown the score of the yet-to-be-performed The Rite of Spring.

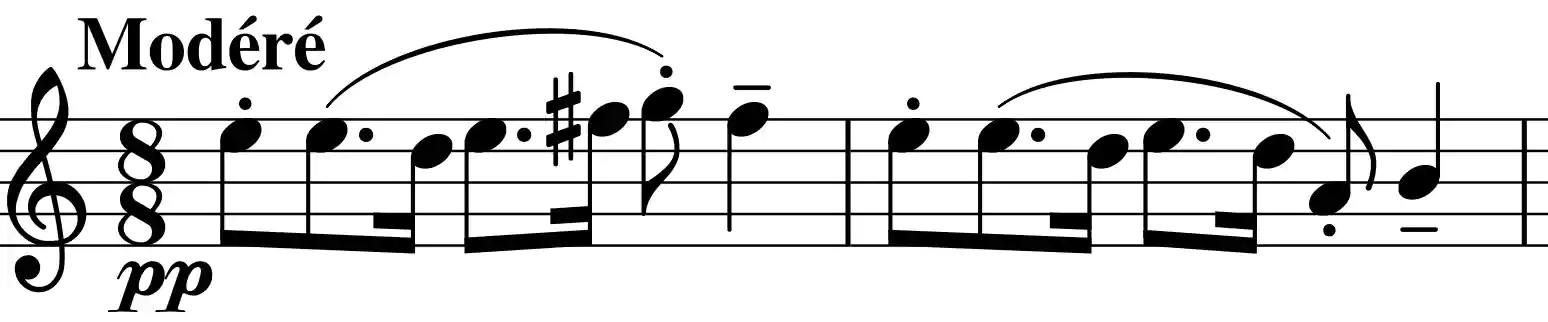

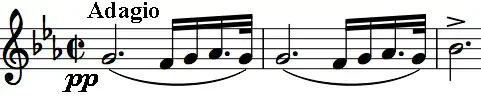

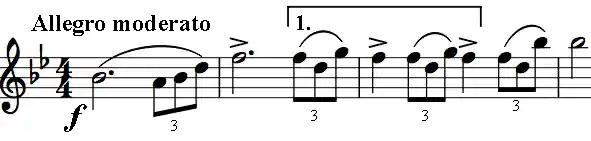

When war broke out in 1914, Ravel was working on his Piano Trio in the French Basque commune of Saint-Jean-de-Luz near to his home town; he completed the work in five weeks before volunteering for military service. He was also working on a piano concerto (Zazpiak Bat) based on Basque themes, which was later abandoned, but whose main theme is identical in rhythm (though half speed) to the opening of the Trio (illustrated). The time signature is an unusual 8/8 – eight quavers in a bar rather than the more usual 4/4 (four crotchets) since the quavers in each bar are grouped 3+2+3. This rocking rhythm is a dominant feature of the movement. Notice also how the theme moves in single note steps until a downward jump of a fourth near the end. The opening themes of the other three movements are similarly constructed—in the second and fourth movements, the jump is of a fifth.

unusual 8/8 – eight quavers in a bar rather than the more usual 4/4 (four crotchets) since the quavers in each bar are grouped 3+2+3. This rocking rhythm is a dominant feature of the movement. Notice also how the theme moves in single note steps until a downward jump of a fourth near the end. The opening themes of the other three movements are similarly constructed—in the second and fourth movements, the jump is of a fifth.

The second movement is in the form of a Scherzo and Trio but mysteriously titled Pantoum. A pantoum is a Malaysian verse form in which two themes are interlocked: the second and fourth lines of each four line stanza become the first and third of the next. Debussy had previously set to music a pantoum-structured poem by Baudelaire, but Ravel appears to be doing something more ambitious. According to Brian Newbould the alternating development of two contrasting ideas in this movement follows a pantoum structure: the skittish opening theme, and the smoother rather breathless one that follows it. Combining this construction with a Scherzo and Trio form leads to an extraordinary passage where the strings continue to play in the Scherzo’s 3/4 time while the piano introduces a new melody for the Trio in 4/2. The movement poses additional problems for the strings with each of a group of rapidly repeated notes having to be played in a different way including left hand pizzicato.

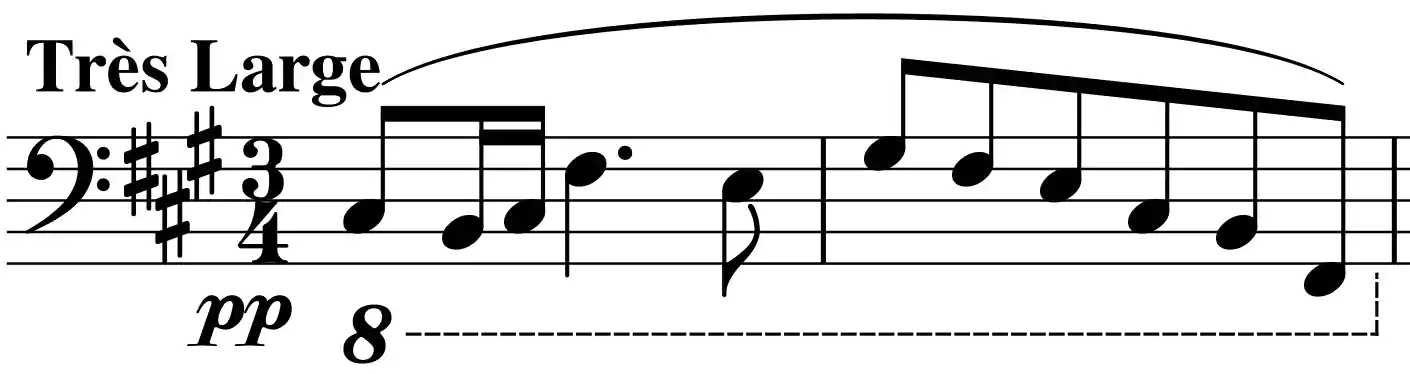

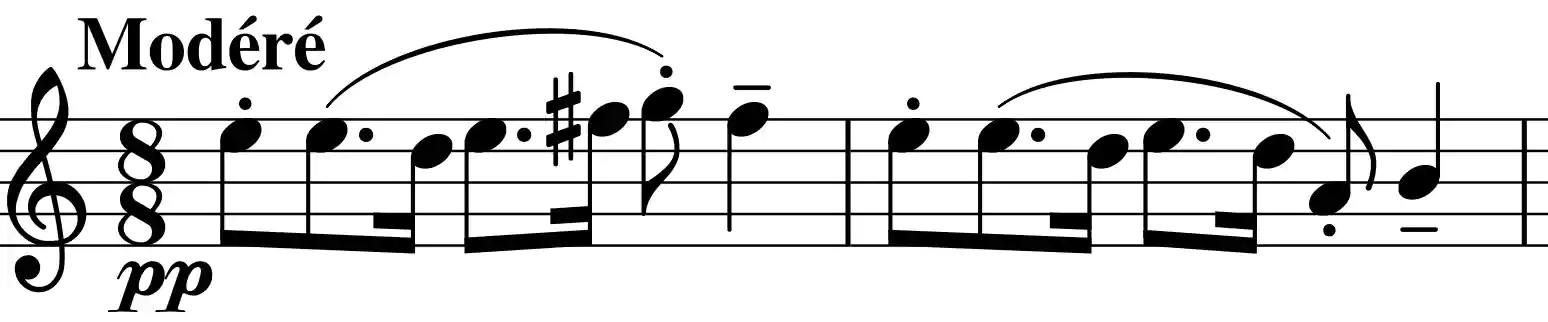

The slow dark Passacaille makes a fine contrast to the scherzo’s scintillations and its theme (illustrated) is a slowed down version of the Pantoum’s opening. The movement is arch-shaped, starting with a single voice, building to a climax and receding back to the solo piano.

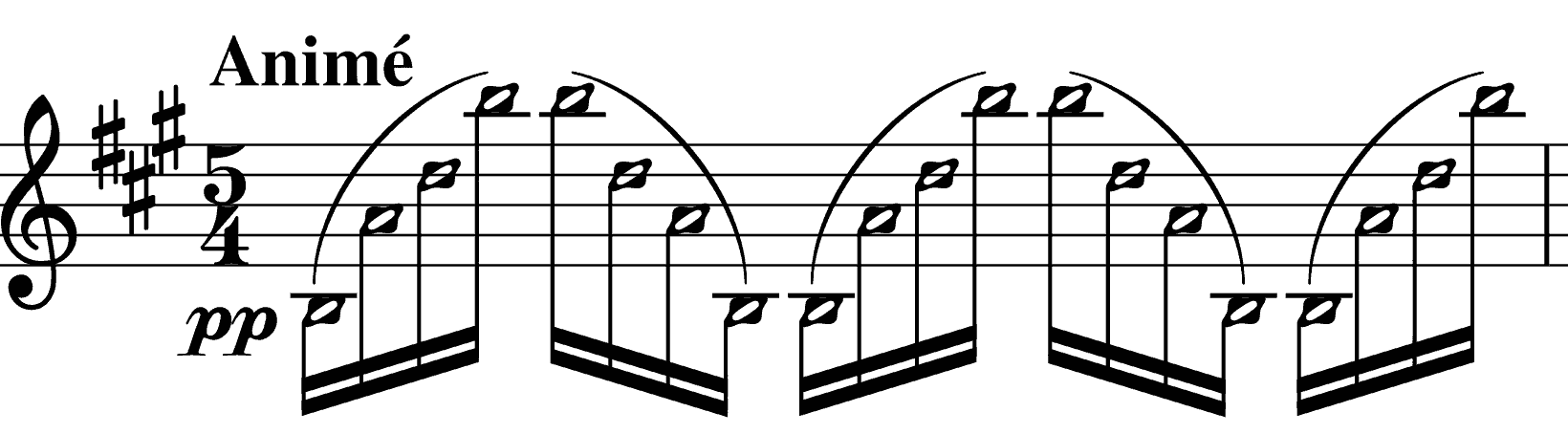

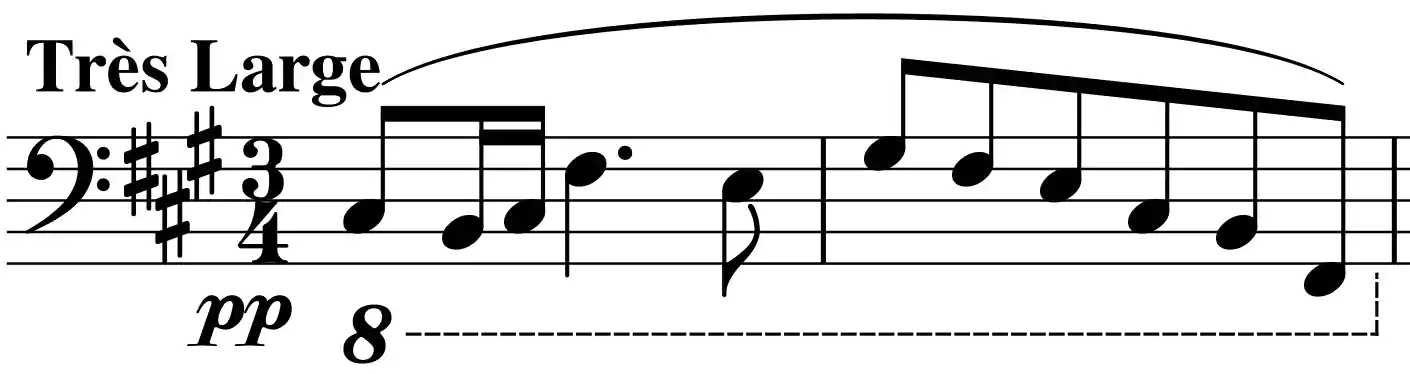

T he Final moves into the major and like the first movement is built on unusual Basque-inspired time signatures – here shifting between 5 and 7 beats in the bar with an occasional 4 or 6 thrown in. The opening texture is unusual and technically demanding for the violinist, who has to play an arpeggio consisting entirely of harmonics (illustrated). The difficulty here is that each of the four fingers has to lightly touch a different string in precisely the right position or the note completely fails to sound.

he Final moves into the major and like the first movement is built on unusual Basque-inspired time signatures – here shifting between 5 and 7 beats in the bar with an occasional 4 or 6 thrown in. The opening texture is unusual and technically demanding for the violinist, who has to play an arpeggio consisting entirely of harmonics (illustrated). The difficulty here is that each of the four fingers has to lightly touch a different string in precisely the right position or the note completely fails to sound.

After he had finished composing the Trio, Ravel’s repeated applications to enlist were rejected on health grounds until finally in March 1916 he was accepted as a driver for the motor transport corps, naming his vehicle Adélaïde after his ballet, sub-titled le langage des fleurs.

Matthew Kaner Piano Trio

Matthew Kaner was born in London in 1986 and studied music at King’s College and composition with Julian Anderson and Richard Baker at the Guildhall. He has been a Professor of Composition at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama since 2013.

His works include the 2022 BBC Proms commission ‘Pearl’ for the BBCSO, Chorus and baritone Roderick Williams setting medieval poetry in a modern translation by Simon Armitage.

His debut solo album of chamber works was released by Delphian Records in November 2022 and was described as revealing ‘a composer deftly able to draw the listener into his far-reaching imaginative world’.

Amongst his upcoming projects is a concerto for violinist Benjamin Baker.

His Piano Trio of 2021 which lasts around 12 mins is in three movements:

1. Glints in the Water

2. Ripples

3. Eroding Lines

The piece was written for Benjamin Baker, Matthias Balzat and Daniel Lebhardt.

Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Piano Trio No.1 in B-flat major, D.898 (1827)

Allegro moderato

Andante un poco mosso

Scherzo & Trio: Allegro

Rondo: Allegro vivace

Schubert’s two Piano Trios date from the final years of his life when, frustrated by his lack of success at opera and dissatisfied with his song writing, he returned to instrumental music, overcoming the daunting shade of Beethoven to compose a series of masterpieces. His two piano trios were written after the octet and the late string quartets (including ‘Death and the Maiden’ and the G major quartet) but before the 2-cello string quintet. The trios are both very substantial works, matching his contemporary ‘Great’ C major symphony in length and musical depth. At that time, Schubert was known to Viennese concert-goers almost exclusively as a writer of songs: many male-voice part songs plus the Erlkönig (and a few others). By the end of 1827 the only public performances of his chamber music had been of just three of his works (including the first Piano Trio) in the Schuppanzigh Quartet’s subscription concerts.

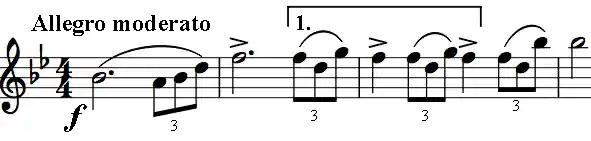

Despite Schubert’s failing health and erratic mood swings, the B-flat Trio is radiant. Robert Schumann wrote of it: “One glance at Schubert’s Trio and the troubles of our human existence disappear and all the world is fresh and bright again.” The glorious opening theme (illustrated) in unison on violin and cello is confident and optimistic. It also contains two ideas, one local, one global, which reappear in various forms throughout the piece. The local idea is the triplet – crochet pattern under [1]. The global idea is the pattern of the first four bars: simply put, “slow, slow, quick, slow”.

The glorious opening theme (illustrated) in unison on violin and cello is confident and optimistic. It also contains two ideas, one local, one global, which reappear in various forms throughout the piece. The local idea is the triplet – crochet pattern under [1]. The global idea is the pattern of the first four bars: simply put, “slow, slow, quick, slow”.

The same pattern reappears immediately in the tender second theme (illustrated) introduced by the cello. After an expansive development of this material Schubert gives us three false starts for the recapitulation in ‘wrong’ keys.

(illustrated) introduced by the cello. After an expansive development of this material Schubert gives us three false starts for the recapitulation in ‘wrong’ keys.

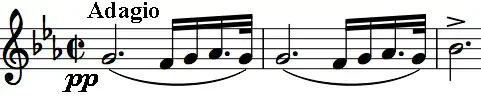

The glorious Andante with its opening cello theme joined rhapsodically by the violin was, incredibly, an afterthought. Schubert originally wrote a slow Adagio, which was posthumously published as a Notturno in E-flat D.897. The Notturno’s opening theme (illustrated) is a slowed down version of the opening of the first movement. It is not clear why Schubert rejected it, but we are lucky that he did since the replacement Andante is one of those movements that you cannot imagine being without – and we do still have the Notturno.

The Notturno’s opening theme (illustrated) is a slowed down version of the opening of the first movement. It is not clear why Schubert rejected it, but we are lucky that he did since the replacement Andante is one of those movements that you cannot imagine being without – and we do still have the Notturno.

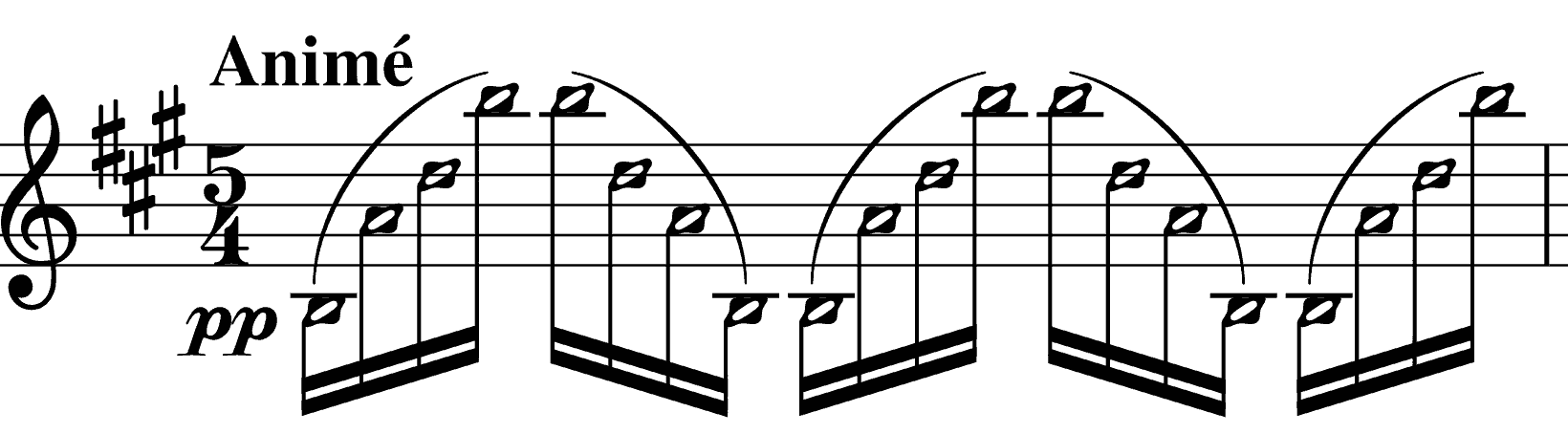

The Scherzo and Trio are based on two dance forms – the Ländler and the waltz. The opening figure of the Scherzo (illustrated) is based on the local triplet-crotchet figure of the first movement, whereas the first four bars of the Trio (illustrated) are in its global ‘slow, slow, fast, slow’ pattern. This global

The opening figure of the Scherzo (illustrated) is based on the local triplet-crotchet figure of the first movement, whereas the first four bars of the Trio (illustrated) are in its global ‘slow, slow, fast, slow’ pattern. This global pattern also appears in 2-bar units in the 8-bar opening of the Rondo last movement (illustrated) with the dotted rhythm providing the ‘quick’ quality.

pattern also appears in 2-bar units in the 8-bar opening of the Rondo last movement (illustrated) with the dotted rhythm providing the ‘quick’ quality.

Programme notes by Chris Darwin (Ravel and Schubertl) and Guy Richardson (Kaner).

See Chris Darwin’s Programme Notes for other works on his web page.

unusual 8/8 – eight quavers in a bar rather than the more usual 4/4 (four crotchets) since the quavers in each bar are grouped 3+2+3. This rocking rhythm is a dominant feature of the movement. Notice also how the theme moves in single note steps until a downward jump of a fourth near the end. The opening themes of the other three movements are similarly constructed—in the second and fourth movements, the jump is of a fifth.

unusual 8/8 – eight quavers in a bar rather than the more usual 4/4 (four crotchets) since the quavers in each bar are grouped 3+2+3. This rocking rhythm is a dominant feature of the movement. Notice also how the theme moves in single note steps until a downward jump of a fourth near the end. The opening themes of the other three movements are similarly constructed—in the second and fourth movements, the jump is of a fifth.

he Final moves into the major and like the first movement is built on unusual Basque-inspired time signatures – here shifting between 5 and 7 beats in the bar with an occasional 4 or 6 thrown in. The opening texture is unusual and technically demanding for the violinist, who has to play an arpeggio consisting entirely of harmonics (illustrated). The difficulty here is that each of the four fingers has to lightly touch a different string in precisely the right position or the note completely fails to sound.

he Final moves into the major and like the first movement is built on unusual Basque-inspired time signatures – here shifting between 5 and 7 beats in the bar with an occasional 4 or 6 thrown in. The opening texture is unusual and technically demanding for the violinist, who has to play an arpeggio consisting entirely of harmonics (illustrated). The difficulty here is that each of the four fingers has to lightly touch a different string in precisely the right position or the note completely fails to sound. The glorious opening theme (illustrated) in unison on violin and cello is confident and optimistic. It also contains two ideas, one local, one global, which reappear in various forms throughout the piece. The local idea is the triplet – crochet pattern under [1]. The global idea is the pattern of the first four bars: simply put, “slow, slow, quick, slow”.

The glorious opening theme (illustrated) in unison on violin and cello is confident and optimistic. It also contains two ideas, one local, one global, which reappear in various forms throughout the piece. The local idea is the triplet – crochet pattern under [1]. The global idea is the pattern of the first four bars: simply put, “slow, slow, quick, slow”. (illustrated) introduced by the cello. After an expansive development of this material Schubert gives us three false starts for the recapitulation in ‘wrong’ keys.

(illustrated) introduced by the cello. After an expansive development of this material Schubert gives us three false starts for the recapitulation in ‘wrong’ keys. The Notturno’s opening theme (illustrated) is a slowed down version of the opening of the first movement. It is not clear why Schubert rejected it, but we are lucky that he did since the replacement Andante is one of those movements that you cannot imagine being without – and we do still have the Notturno.

The Notturno’s opening theme (illustrated) is a slowed down version of the opening of the first movement. It is not clear why Schubert rejected it, but we are lucky that he did since the replacement Andante is one of those movements that you cannot imagine being without – and we do still have the Notturno. The opening figure of the Scherzo (illustrated) is based on the local triplet-crotchet figure of the first movement, whereas the first four bars of the Trio (illustrated) are in its global ‘slow, slow, fast, slow’ pattern. This global

The opening figure of the Scherzo (illustrated) is based on the local triplet-crotchet figure of the first movement, whereas the first four bars of the Trio (illustrated) are in its global ‘slow, slow, fast, slow’ pattern. This global pattern also appears in 2-bar units in the 8-bar opening of the Rondo last movement (illustrated) with the dotted rhythm providing the ‘quick’ quality.

pattern also appears in 2-bar units in the 8-bar opening of the Rondo last movement (illustrated) with the dotted rhythm providing the ‘quick’ quality.