W.A. Mozart (1756-1791) String Quartet in G K.387 (1782)

Allegro vivace assai

Minuetto & Trio – Allegro

Andante Cantabile

Molto Allegro

The early 1780s were a time of great change for Mozart. He had had a resounding success in Munich with his opera Idomeneo, a success which made him resentful of his junior status in the service of the Salzburg Archbishop Colloredo. Mozart forced a break with the Archbishop, allowing a move from Salzburg to Vienna in 1781, to the annoyance of his father Leopold. Mozart was also occupied in the Weber household, transferring his affections from the unobtainable Aloysia to her sister Constanza and marrying her in August 1782, further souring relations with his father. Eventually, in the summer of 1783, Mozart and his wife made a three-month conciliatory visit to his father in Salzburg, leaving behind their infant son Raimund Leopold, who died shortly afterwards. Despite these emotional upheavals, the musical freedom gained by the move to Vienna allowed Mozart’s composing to flourish. His opera Die Entführung and the “Haffner” Symphony rocketed him to fame.

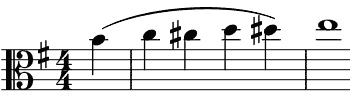

During this period, Mozart was working hard on the set of six quartets that he would dedicate to Haydn. These quartets were directly inspired by Haydn’s Opus 33 set and famously were generously praised by Haydn, who in turn was inspired by Mozart in the writing of his subsequent quartets. Unlike Beethoven, Mozart left very little trace of his process of composing. Constanza remembered how he would roam, preoccupied, around the house, apparently doing nothing; then, when he finally started to ‘work’, writing down a composition, he would chatter away to her about domesticities. But some problems were too knotty to be sorted even by Mozart’s internal thought processes; one such is the beginning of the second half of this G major quartet’s last movement. The viola introduces a rising chromatic motif, which is then passed between cello and viola as the music modulates. Early versions of the quartet show that Mozart initially gave these sequences entirely to the cello, with the other three instruments providing slow-moving chords. But he could not find a sufficiently elegant solution to the problem of how to assign the notes of these chords to the upper three instruments. After three drafts, he eventually hit on the solution of alternating the crotchets between the viola and cello, leaving only the two violins to fill in the harmonies. For the listener, there is not a lot of difference, but Mozart was writing for Haydn.

introduces a rising chromatic motif, which is then passed between cello and viola as the music modulates. Early versions of the quartet show that Mozart initially gave these sequences entirely to the cello, with the other three instruments providing slow-moving chords. But he could not find a sufficiently elegant solution to the problem of how to assign the notes of these chords to the upper three instruments. After three drafts, he eventually hit on the solution of alternating the crotchets between the viola and cello, leaving only the two violins to fill in the harmonies. For the listener, there is not a lot of difference, but Mozart was writing for Haydn.

As an illustration of the thematic unity of this quartet, look at where this chromatic motif crops up. It has its origins in the rising chromatic quavers (*) of the second bar of the first movement, and the corresponding falling quavers of bar 4. Our attention is drawn to them by a subito piano and they bring chromatic interest to the straightforward key of G major. The motif reappears

illustration of the thematic unity of this quartet, look at where this chromatic motif crops up. It has its origins in the rising chromatic quavers (*) of the second bar of the first movement, and the corresponding falling quavers of bar 4. Our attention is drawn to them by a subito piano and they bring chromatic interest to the straightforward key of G major. The motif reappears in the bizarrely alternating forte – piano rising crotchets of the Minuetto, and again, inverted,

in the bizarrely alternating forte – piano rising crotchets of the Minuetto, and again, inverted, near the beginning of the last movement against accompanying quavers in the viola.

near the beginning of the last movement against accompanying quavers in the viola.

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) String Quartet Op. 44 No.2 in E minor (1837)

Allegro assai Appassionato

Scherzo – Allegro di molto

Andante

Presto agitato

Felix Mendelssohn was born into an intellectual and affluent household: his grandfather Moses was the pre-eminent Jewish philosopher of the Enlightenment, and both his father and mother’s family were bankers. Felix and his sister Fanny were outstandingly precocious and were driven hard by their parents – their day started at 5 am at the latest. In 1818 the 9-year old Felix publicly performed a Dussek piano concerto from memory, and his first datable composition was performed in Berlin the same year. His copious early compositions outshone even those of Mozart. When Mendelssohn was 12 he played for Goethe who had also heard the young Mozart. Goethe was impressed: “…what [Mendelssohn] already accomplishes bears the same relation to the Mozart of that time that the cultivated talk of a grown-up person bears to the prattle of a child.” At the age of 16 he produced his first undoubted masterpiece, his String Octet Op 20, incidentally at the same time as a metrically accurate German translation of a comedy by Terence which was published by his tutor the following year!

Mendelssohn’s string quartets fall into four groups: an early (even for Mendelssohn) quartet from 1823; the Op 12 & 13 quartets written in 1829 & 1827 respectively; the three Op 44 quartets including today’s from 1837-8, and finally the Op 80 quartet, a personal outpouring of grief written in 1847 in response to Fanny’s unexpected death, and only a few months before his own. The A minor Op 13 quartet appeared shortly after Beethoven’s late quartets were published; Mendelssohn studied them closely and incorporated many compositional techniques especially from Op 132 & 135 into his Op 13, giving us an interesting link between “classical” and “romantic” quartet writing.

Mendelssohn started work on today’s E-minor quartet in the spring of 1837 while on honeymoon, with his young French bride Cécile (10 years his junior and “fresh, bright and even-tempered” in Fanny’s view); he finished it in Frankfurt on 18 June. That October it was given its first performance by a quartet led by Ferdinand David who coincidentally had been born a year after Mendelssohn in the same house in Hamburg.

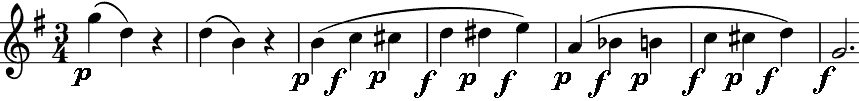

The first movement opens with syncopated crotchets pushing forward, and an optimistically rising theme on the first violin. Soon an even more energetic figure appears – unison semiquavers in all four instruments, which are subsequently fragmented and tossed between the players. Some repose and reflection comes with a tender theme from the first violin (illustrated). Mendelssohn develops and combines these contrasting ideas with apparently effortless fluency, ending tranquillo in the major with the two main themes happily reconciled.

from the first violin (illustrated). Mendelssohn develops and combines these contrasting ideas with apparently effortless fluency, ending tranquillo in the major with the two main themes happily reconciled.

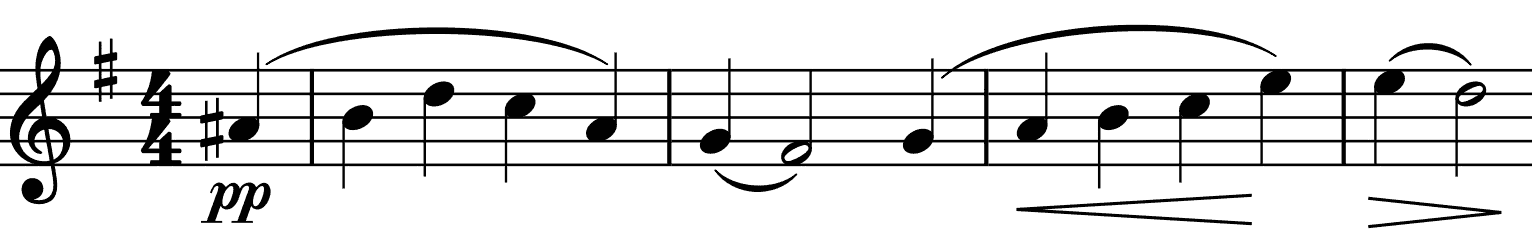

The E-major Scherzo is heir to the light, staccato, tripping scherzo writing of his Octet and Midsummer Night’s Dream overture. The G-major Andante also moves onward (Mendelssohn warns the players “This piece must never be allowed to drag”) with two bars of fluid, pulsing semiquavers from the second violin stretching and opening the windows to allow in the first violin’s beautiful song. It was written on his honeymoon after all!

The last movement opens with a restless figure in the minor key; relentlessly energetic quavers carry us along until we reach this expansive theme in the major (illustrated). The quavers are persuaded to go into the major for a while too, but return to the minor and power on tirelessly to a triumphant conclusion.

relentlessly energetic quavers carry us along until we reach this expansive theme in the major (illustrated). The quavers are persuaded to go into the major for a while too, but return to the minor and power on tirelessly to a triumphant conclusion.

Béla Bartók (1881-1945) String Quartet No 4 (1928)

Allegro

Prestissimo, con sordino

Non troppo lento

Allegretto pizzicato

Allegro molto

Bartók’s third and fourth quartets were written within a year of each other, fully ten years after his second quartet. In July 1927 Bartók heard Alban Berg’s Lyric Suite for string quartet at a concert in Germany. According to Stephen Walsh in his BBC guide to Bartók’s Chamber Music, this was the likely stimulus for Bartók returning to quartet writing. Berg had incorporated Schoenberg’s atonality into a wide range of techniques, producing extreme contrasts of mood, texture and tempo, whilst still aiming for the traditional virtue of beauty of sound. Bartók married Berg’s eclectic approach to his own enthusiasm for Hungarian folk-music, with its powerful rhythms and harsh, dissonant sounds. Berg is said to have found the harsh energy of Bartók’s fourth quartet ‘too cacophonous’.

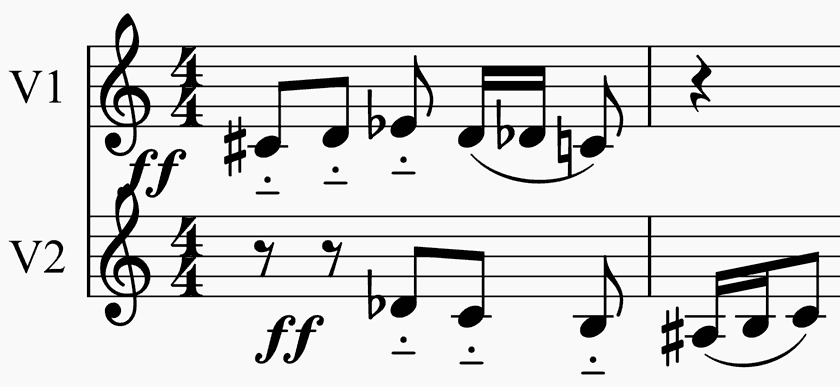

A significant theme in the first and last movement of the fourth quartet is a violent 6-note arch-shaped motif which first occurs near the beginning. The motif moves in semitones – one of the characteristic intervals of Hungarian folk-music. But notice also that the original motif in the first violin is immediately echoed by an inverted version in the second violin, to produce a powerfully dissonant series of seconds with the original.

6-note arch-shaped motif which first occurs near the beginning. The motif moves in semitones – one of the characteristic intervals of Hungarian folk-music. But notice also that the original motif in the first violin is immediately echoed by an inverted version in the second violin, to produce a powerfully dissonant series of seconds with the original.

A major structural feature of Bartók’s Fourth Quartet is that the five movements form an arch-like structure ABCBA, with the middle, slow movement the heart of the work. Bartók described the quartet as follows:

‘The slow movement is the nucleus of the piece, the other movements are, as it were, bedded around it: the fourth movement is a free variation of the second one, and the first and fifth movements are of the identical thematic material. Metaphorically speaking, the third movement is the kernel, movements I and V the outer shell and II and IV, as it were, the inner shell.’

Although the fourth movement is a ‘free variation of the second one’, the two movements have very different sounds. The second is extremely fast and muted, like fluttering moths but with a variety of strange sounds – slithering semitones, slides and strums; the fourth is from a land of darting invertebrates, punctuated by the ‘Bartók pizzicato’ where the string is pulled so that its release slaps the fingerboard.

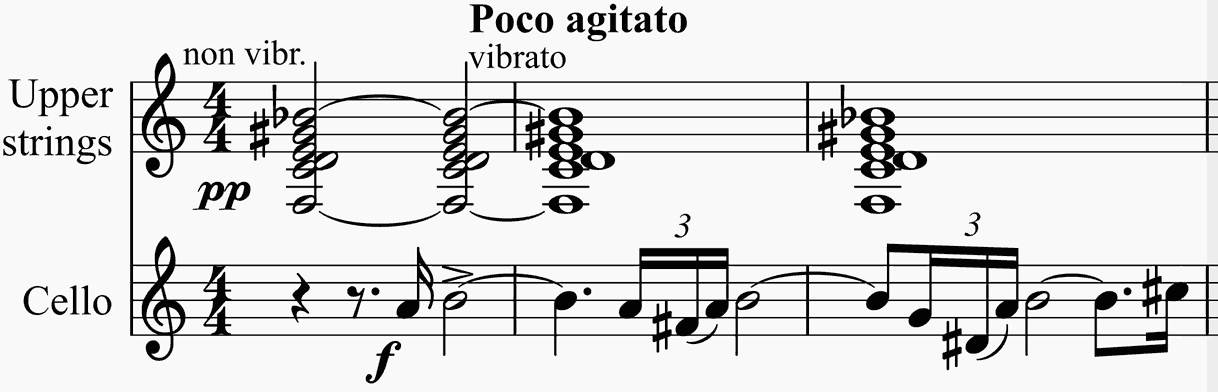

Between all this restlessness, the third movement is a very different world – the stillness of Bartók’s ‘night music’. The upper strings hold long chords against the cello’s initial plaintive melody. The slowly-changing chords become more dissonant, the melody more decorated and the tempo more agitated before settling back down again. The chords do not traditionally harmonise the melody, rather they supply notes that the melody lacks. For example, after about 20 bars, the held chord has 6 of the notes of the chromatic scale, the cello melody the other six – a striking example of Bartók’s intellectual rigour within a movement of undeniable beauty and emotional power.

against the cello’s initial plaintive melody. The slowly-changing chords become more dissonant, the melody more decorated and the tempo more agitated before settling back down again. The chords do not traditionally harmonise the melody, rather they supply notes that the melody lacks. For example, after about 20 bars, the held chord has 6 of the notes of the chromatic scale, the cello melody the other six – a striking example of Bartók’s intellectual rigour within a movement of undeniable beauty and emotional power.

The exciting last movement lashes us with harsh chords and leads us in a wild peasant dance throwing around and finally flinging in our face the 6-note motif that we started with.

See Chris Darwin’s Programme Notes for other works on his web page.